Op/Ed

Faith Gong: Breathless

I’ve seen several articles lately in which mental health professionals explain the emotions that humankind is experiencing right now — when the worldwide death toll from the COVID-19 virus continues to rise and the social distancing guidelines under which we have been placed stretch out indefinitely — as grief. Collective grief. If this is the case, then it looks like I’ve reached the anger stage.

I don’t consider myself an angry person, but I suppose we are all angry people; some of us just deal with or bury our anger better than others. My own anger is usually hidden deep beneath layers of trying to be “nice” and desperately wanting everyone to like me. There’s something about this global pandemic, however, which is causing my anger to bubble to the surface.

What am I angry at? It’s not that our family’s life has ground to a standstill, our movements confined to our home, and our social interactions limited to digital platforms. We spent a lot of time together as a family before quarantine, we’ve been homeschooling our children for the past four years, our homestead comprises twelve acres and a quarter-mile driveway, I enjoy having my husband around the house, and I’m an introvert. I have very little to complain about in this arena, other than bemoaning the increased time we’re spending in front of screens to maintain extra-familial relationships.

My anger is a result of our family’s experience with illness — illness that may or may not be COVID-19 — over the past three weeks.

It began during what I think of now as the “transitional week.” The week of March 15 started much like any other week here in Vermont, albeit with a heightened awareness that COVID-19 was bearing down upon us. By the end of the week, everything had started to shut down. During this week my husband, our four-month-old son, and I began to have some sniffles. Sniffles were not, at that time, considered an indication of COVID-19. We wondered whether we were getting colds or allergies and went about our business.

On March 22, my husband and I could barely get out of bed. Both of us felt worse than we’d felt in years: fever, chills, body aches, exhaustion, nausea, pounding headaches, and, for me, chest pressure. Our son’s sniffles had transformed into an awful croupy cough. We called all three of our doctors and were informed that none of us met the CDC criteria for COVID-19 testing, as we were not considered high-risk.

Although the CDC didn’t consider our son high-risk, in January he’d spent two weeks in the hospital — one week intubated in the ICU — after a mysterious respiratory infection caused him to stop breathing, so we considered him high-risk. When we inquired about having him tested for flu or RSV, we were told that these tests were off the table, since they use the same swabs and medium as the COVID-19 test and require health professionals to don the same protective gear.

We didn’t push it; we understood the greater public health landscape. Thankfully, after a week of “steamy bathroom therapy,” our son’s cough improved.

My husband and I, after our initial extreme symptoms, were also feeling better. We met the CDC guidelines for stopping home isolation: We’d had no fever for over 72 hours, our other symptoms had improved, and at least 7 days had passed since our symptoms first appeared.

On day eight, the slight cough that was my one persistent symptom ramped up, accompanied by chest pressure and the feeling that I couldn’t get breath all the way down to my belly. I called my doctor, who referred me for COVID-19 testing the next day. The policy had changed: Vermont had managed to procure more tests and doctors were now testing patients with mild-to-moderate symptoms. My doctor said that they’d been seeing COVID-19 behave much as I’d described, with an abatement of symptoms followed by a resurgence 7-10 days later.

Driving to my test at Porter Hospital was surreal. I hadn’t left our driveway in over a week. The town was empty and quiet. The test, performed through the rolled-down window of my car in the Porter parking lot by a man in full protective gear, was quick and easy. Four other cars waited in line behind me.

Three days later, the results of my test arrived: COVID-19 was undetected. This should have come as a relief, but it didn’t. My symptoms, which now included violent coughing spells, chest pain, and breathlessness, continued. My doctor informed me that the COVID-19 test may have a 25-30% false negative rate, as it was fast-tracked before its accuracy was known; it’s useful as a public heath metric more than a diagnostic tool. “I don’t care about the test,” she said, prescribing me an inhaler and high-dose Vitamin C. “If it looks like a duck and quacks like a duck, I’m going to treat it like a duck.”

I was left short of breath, confused, and angry.

Angry that there weren’t enough tests at the outset for us to be tested sooner.

Angry that information about the course of this illness and its symptoms is still spotty enough that the CDC guidelines might recommend someone leave isolation just before their symptoms really get going.

Angry that the tests we have may be so inaccurate that up to a third of infected people could be told that they’re fine and miss out on timely treatment.

This anger is primarily self-centered, as anger tends to be. I do realize that I have much to be thankful for. The test may be right; I may not have COVID-19, but another virus that’s making an otherwise healthy woman in her early 40s feel like an aging lifelong smoker. Even if I do have COVID-19, I will likely recover. My doctor has been amazing. My husband is in better shape than I am, and our five children are doing fine.

But I’m also angry on behalf of all the other people — many sicker than I — who will experience these frustrations with access to testing and clarity regarding test results and isolation timelines.

There are those who would blame these issues on the government or the medical establishment. I don’t; I’m willing to extend grace to all involved. We’re dealing with a new virus, there’s still much we don’t know, and I believe that everyone’s trying to make the best decisions possible based on the available information and resources. Everyone is groping in the dark; this pandemic has left us all breathless.

Which leaves me with no target for my anger but the virus itself. This is problematic; as I learned back in January when our son was so sick, it’s unproductive to be angry at a virus, like screaming at the wind or kicking a rock. The virus doesn’t care.

But anger itself is an unproductive emotion, one that’s best acknowledged and passed through on your way to something better. When I distill my anger down to its source, I see that what I’m really angry at is my own helplessness in the face of circumstances that I can’t control, and that I have no map for navigating.

When we talk about our collective grief over COVID-19, this is what we’re really talking about, isn’t it? We grieve for those who are ill and dying, of course, but we also grieve how this pandemic has smashed our illusions of safety and control. Social distancing guidelines have stripped away everything we usually turn to for comfort: food, shopping, community, entertainment, work, recreation, and good hair.

As my body moves through this illness, and as my soul moves through this anger, the question I keep asking myself is: What am I clinging to? In the absence of my usual illusions of control and security, what remains? It’s a question worth asking for us all, as the world tries to heal.

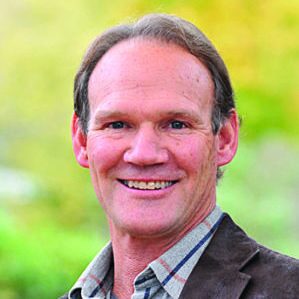

Faith Gong has worked as an elementary school teacher, a freelance photographer, and a nonprofit director. She lives in Middlebury with her husband, five children, assorted chickens and ducks, one feisty cat, and one anxiety-prone labradoodle. In her “free time,” she writes for her blog, The Pickle Patch.

More News

Op/Ed

ICE and CBP: Legislators could do more to protect Vermonters’ rights

“[Legislators] would be wise to also reconsider how to protect Vermonters in the near-cert … (read more)

Op/Ed

Legislative Report: We must act now to address food insecurity

“I strongly believe we have an opportunity in this legislative session to strengthen our f … (read more)

Op/Ed

Ways of Seeing: America’s reign of cruelty is not new

“The government-sanctioned violence that we are witnessing across the nation has historica … (read more)